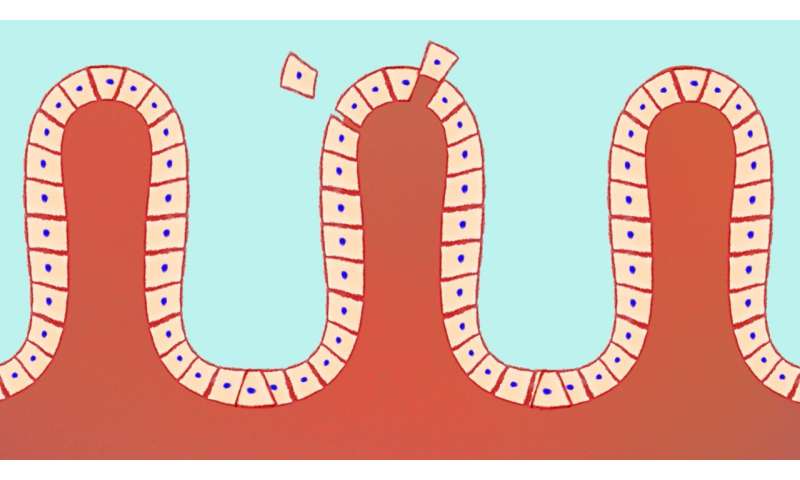

Cells on the inner surface of the intestine are replaced every few days. But, how does this work? It was always assumed that cells leave the intestinal surface because excess cells are pushed out.

In the journal Science, researchers from the Hubrecht Institute and AMOLF show that this is not correct. In reality, the situation is exactly the opposite: the cells do not push, but pull at each other. These pulling forces lead to the removal of the weakest cells. This insight gives a new perspective on how a malfunctioning intestine can lead to disease or infection.

Pulling rather than pushing

The general idea was as follows: old and malfunctioning cells in the intestinal surface move to the exit like packages on a conveyor belt in a distribution center. Cells “push” each other out as they accumulate.

It turns out to be different. Researchers Daniel Krueger and Kasper Spoelstra show that the cells are not under pressure, but under tension. This tension arises from cells “pulling” at each other. This is comparable to a game of tug of war, but then played by cells and their neighbors. This tug-of-war game turns out to be essential to determine which cells are the weakest, and therefore need to leave the intestine.

To get to these new insights, the research groups of Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute), Sander Tans (AMOLF) and Jeroen van Zon (AMOLF) work with so-called intestinal organoids. These are miniature versions of the intestine grown in the lab. One of the advantages of these organoids is that researchers can easily manipulate and study them under a microscope.

Pulling forces exerted by cells on one another are essential for proper intestinal function. Cells that cannot generate sufficient pulling forces are removed from the intestine. These cells form a risk of improper closure of the barrier between the inside and outside of the intestines, which can lead to inflammation.

Experiments

Researchers Daniel and Kasper influenced the tug of war game played by cells in the organoids in different ways. Firstly, they conducted a series of experiments making cells weaker or stronger by manipulating them with light or by genetic manipulation.

-

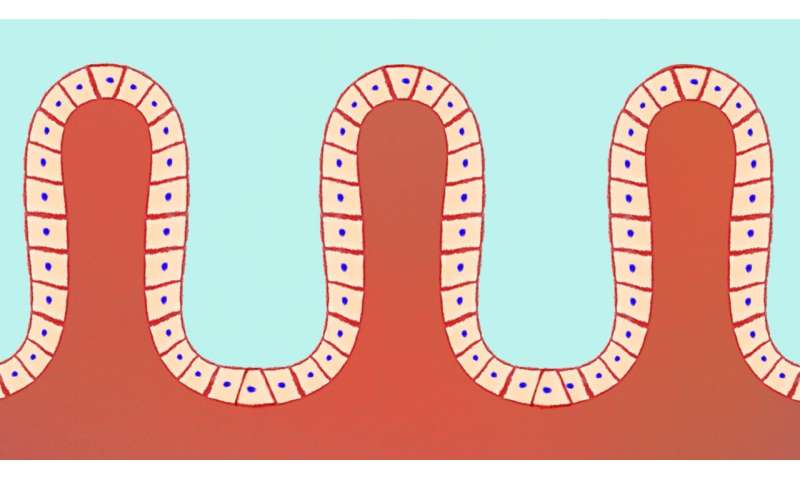

Gut cells form millions of tiny tentacle-shaped structures called villi, to better absorb nutrients. Credit: Bruno van Wayenburg

-

Cells on the inner surface of the intestine are replaced every few days. Credit: Bruno van Wayenburg

Whenever they combined stronger and weaker cells in one organoid, they noticed that weaker cells disappeared much more often from the organoid than stronger cells. Secondly, they conducted experiments weakening individual cells with a laser.

Cells weakened in this manner tended to be extruded within one hour. Both experiments show that whenever cells are weaker than their neighbors—and are therefore losing the tug of war game—they are quickly removed from the intestine.

A closer look at intestinal diseases

Pulling forces between cells in the intestinal surface also has medical consequences. The researchers also studied organoids with a genetic abnormality for the disease congenital tufting enteropathy. This disease has a negative effect on the development of the intestinal surface in newborns, sometimes leading to irreparable damage to the intestine.

The researchers demonstrated that cells with this particular genetic abnormality show a disrupted tug of war behavior; they are exerting too much pulling force on each other.

Now that it is clear that cells leave the intestinal surface because of their ability to exert pulling forces, the researchers expect that follow-up studies will be conducted using tissue from patients with intestinal abnormalities, and also on forces between cells in other organs.

More information:

Daniel Krueger, et al, Epithelial tension controls intestinal cell extrusion, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr8753

Citation:

Intestinal surface cells pull rather than push to remove weak neighbors, research reveals (2025, September 4)

retrieved 4 September 2025

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-09-intestinal-surface-cells-weak-neighbors.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.